*Content has been reviewed by Dr. John Sievenpiper, MD, PhD (Associate Professor, Department of Nutritional Sciences, University of Toronto); Last updated June 2024

Obesity is a complex, progressive, and relapsing chronic disease characterized by abnormal or excessive body fat accumulation that impairs health (1).

- Obesity is a Complex Disease. There are many different risk factors for obesity, such as genetics, dietary habits, level of physical activity, gut (microflora) health, environmental factors, sleep patterns, and mental stress. The amount of body fat and its distribution in the body are more accurate indicators of obesity rather than body weight, which also accounts for muscle and bodily fluids.

- Diet and Obesity. Research suggests eating too many calories from all sources – sugars, starches, proteins, fats, and alcohol – and not using these calories through normal body functions, movement, and physical activity, can increase the likelihood of storing the excess calories as fat in the body. Other aspects, such as our relationships with food, affordability, culture, and eating behaviours, also play a crucial role in obesity.

- Sugars and Obesity. The highest level of scientific evidence has shown that the effect of sugars on obesity is mediated by food source and energy intake.

- Nutrition in Obesity Management. Long-term diet modifications, such as reducing the frequency or portion size of foods and beverages higher in calories from sugars and fats, and increasing consumption of nutrient-dense foods like fruits and vegetables, can help reduce intake of excess calories, and eventually lead to weight loss. It is important that these modifications are personalized to meet individual values and preferences.

Obesity is a Complex Disease

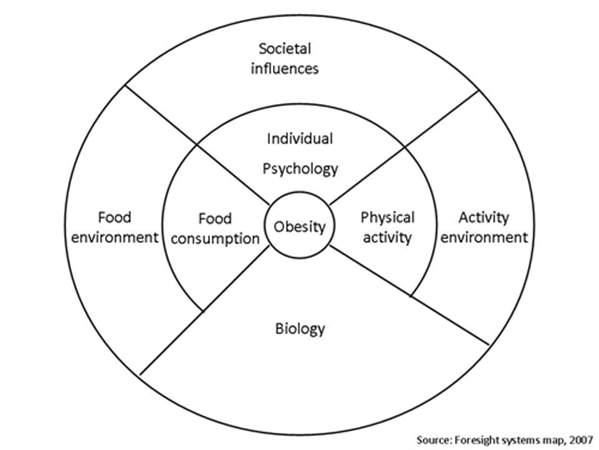

Many factors contribute to the risk of obesity including biology (e.g. genetics), diet (e.g. food consumption), individual activity (e.g. physical activity), individual psychology (e.g. emotional stress, depression), activity environment, and societal influences (1,2).

Having obesity increases risk of several chronic diseases, including diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, musculoskeletal disorders, and some cancers (1).

Obesity Canada recommends that screening for obesity should be performed regularly by measuring both Body Mass Index (BMI) and waist circumference (1).

- The amount of body fat and its distribution in the body are more accurate indicators of obesity rather than using body weight, which also accounts for muscle and bodily fluids.

- Waist circumference helps identify abdominal obesity, which reflects increased fat around major organs (3-6). Having excess fat around major organs such as the liver, heart, and kidney (called visceral fat) has been shown to be a direct contributor to metabolic diseases such as heart disease, diabetes, and cancer (7).

The Role of Diet in the Development of Obesity

Diet is just one factor that may increase risk for obesity. It is important to remember that neither excess calorie intake, poor food choices, or eating habits is the sole cause for weight gain given the number of factors involved.

An individual may experience weight gain when more energy (calories) is consumed from all foods and beverages than is expended for normal bodily functions (e.g., breathing, digestion, pumping blood), daily movement and physical activity (2).

Fluctuations in energy balance (higher or lower energy intake relative to expenditure) within a meal, day or week are normal and will not necessarily lead to a persistent change in body fat. However, increases in energy intake relative to expenditure (i.e., positive energy balance) over a long period of time may increase the likelihood of the unused calories being stored as fat in the body.

Data from Statistics Canada indicate that a higher consumption of calories independent of the food source increases risk of obesity (8).

Do Sugars Play a Role in Developing Obesity?

The totality of the best scientific evidence have shown that the effect of sugars on weight gain and body fatness is influenced by food source and energy intake.

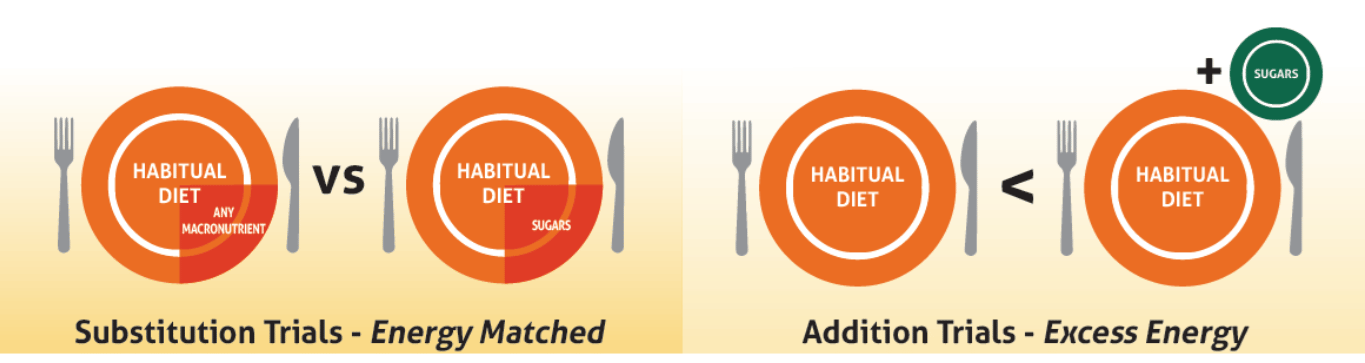

Findings from a recent systematic review and meta-analysis (SRMA) found that (9):

- Findings differed depending on whether sugars-containing foods or beverages were consumed on top of the regular diet (i.e. providing excess energy) or whether sources of sugars were swapped for other foods with no change to energy intake (i.e. energy matched conditions). (See diagram below)

- Food source also mattered – excess energy from sugars-sweetened beverages increased adiposity, whereas most other food sources had no effect, and some showed decreases, such as fruits.

- The authors suggest that the differences in findings may be partly explained by the food matrix, such as the presence or absence of fibre, in the different food sources (9,10).

These findings are consistent with other SRMAs (11-19), and highlight the importance of focusing on foods, dietary patterns, and overall calorie intake when it comes to weight management, rather than focusing solely on limiting sugars.

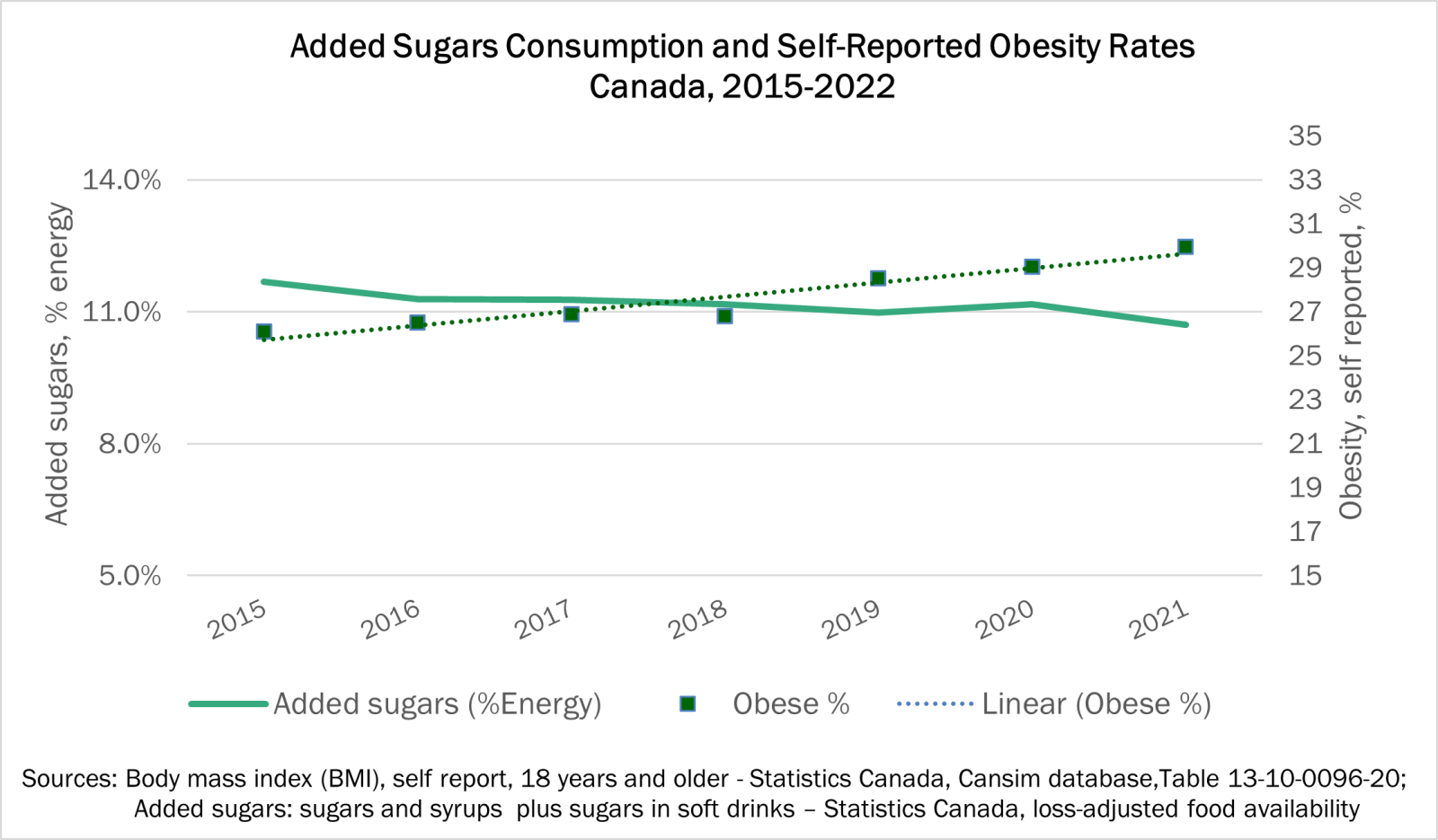

Trends in per capita (per person) added sugars consumption based on loss-adjusted market availability in Canada plotted against rates of obesity indicate an inverse relationship; as rates of obesity continue to increase, consumption of added sugars has declined (see graph below).

Figure: Added sugars based on Statistics Canada Availability Data; Obesity rates determined by measured body mass indices from the Canadian Health Measures Survey.

Nutrition in Obesity Management

Nutrition is not just the food we eat, but also includes our relationships with food, affordability, culture, and eating behaviours.

From a diet perspective, talking to a registered dietitian may be helpful to determine how to make changes to adopt a healthier dietary pattern that can be sustained. Dietitians can help develop a personalized plan to assess and address the root causes of obesity and provide support for behavioural change (e.g. nutrition and exercise) and other intervention strategies (e.g. mental support, medication, etc.) as needed.

Furthermore, it is quite difficult to manage obesity or lose weight only by “eating less calories”, because of the strong biological mechanisms in the body to act against weight loss, as well as other environmental and social factors (1). Getting enough sleep and following the Canadian 24-Hour Movement Guidelines to incorporate physical activity into daily routines can also help maintain a healthy weight.

Some suggestions related to diet include:

- Selecting nutrient-dense foods more often, including whole fruits and vegetables, whole grains, legumes, and lean meats, and less often of other options such as sugar-sweetened beverages and fatty meats.

- Reducing the portion size and/or frequency of snacks that are higher in calories, sugars, saturated fat, and sodium. These foods can be enjoyed as occasional treats rather than every day.

- Choosing water more often to quench thirst and enjoying sugars-sweetened beverages occassionally.

- To reduce the calories from beverages, individuals could:

- Mix sweetened carbonated drinks with water

- Add lemon wedges or small amounts of 100% fruit juice to water to provide varieties in flavour.

- Choosing plain coffee or tea more often and adding milk and/or a small amount of sugar to suit individual tastes rather than purchasing pre-prepared hot and cold coffee and tea beverages.

For more information, additional resources include:

- Infographic - Energy Balance and Body Weight

- Factsheet - Effect of Sugars on Metabolic Disease Risk Factors

- Factsheet - Frequently Asked Questions: Sugars and Obesity

- Carbohydrate News - The Not So Toxic Truth About Sugar

- Video - "Does Sugar Make You Fat?" featuring Dr. Nick Bellissimo and registered dietitian Christy Brissette

Recent news items include:

- May 2023 - Food Sources and Calories Mediate the Effect of Sugars on Obesity

- January 2022 - New Fact Sheet: Effect of Sugars on Metabolic Disease Risk Factors

- November 2017 - Are Foods and Beverages Reduced in Sugars Also Reduced in Calories?

References

- Obesity Canada. Canadian Adult Obesity Clinical Practice Guidelines [Internet]. Edmonton: Obesity Canada; 2022 [cited 2024 Mar 4].

- World Health Organization. Overweight and Obesity [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2024 Mar 1 [cited 2024 Mar 4].

- Neeland IJ, Ross R, Després JP, Matsuzawa Y, Yamashita S, Shai I, Seidell J, Magni P, Santos RD, Arsenault B, Cuevas A, Hu FB, Griffin B, Zambon A, Barter P, Fruchart JC, Eckel RH; International Atherosclerosis Society; International Chair on Cardiometabolic Risk Working Group on Visceral Obesity. Visceral and ectopic fat, atherosclerosis, and cardiometabolic disease: a position statement. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2019 Sep;7(9):715-25.

- Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Daniels SR, Donato KA, Eckel RH, Franklin BA, Gordon DJ, Krauss RM, Savage PJ, SmithJr SC, Spertus JA, Costa F. Diagnosis and management of the metabolic syndrome: an American Heart Association/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Scientific Statement. Circulation. 2005;112:2735-52.

- International Diabetes Federation. The IDF consensus worldwide definition of metabolic syndrome. Brussels: International Diabetes Federation; 2006.

- World Health Organization. Definition, Diagnosis, and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus and its Complications: Report of a WHO Consultation. Part I: Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1999.

- World Health Organization. Noncommunicable Diseases: Risk Factors [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2024 [cited 2024 Mar 4].

- Langlois K, Garriguet D, Findlay L. Diet composition and obesity among Canadian adults. Health Rep. 2009;20(4):11-20.

- Chiavaroli L, Cheung A, Ayoub-Charette S, Ahmed A, Lee D, Au-Yeung F, Qi X, Back S, McGlynn N, Ha V, Lai E, Khan TA, Mejia SB, Zurbau A, Choo VL, de Souza RJ, Wolever TMS, Leiter LA, Kendall CWC, Jenkins DJA, Sievenpiper JL. Important food sources of fructose-containing sugars and adiposity: A systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled feeding trials. Am J Clin Nutr. 2023;117(4):741-65.

- Wang Y, Chiavaroli L, Roke K, DiAngelo C, Marsden S, Sievenpiper J. Canadian Adults with Moderate Intakes of Total Sugars have Greater Intakes of Fibre and Key Micronutrients: Results from the Canadian Community Health Survey 2015 Public Use Microdata File. Nutrients. 2020;12(4):1124.

- Te Morenga L Mallard S, Mann J. Dietary sugars and body weight: systematic review and meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials and cohort studies. BMJ. 2012 Jan;346:e7492.

- Rippe JM, Angelopoulos TJ. Relationship between added sugars consumption and chronic disease risk factors: current understanding. Nutrients. 2016;8(11):697.

- Khan TA, Sievenpiper JL. Controversies about sugars: Results from systematic reviews and meta-analyses on obesity, cardiometabolic disease and diabetes. Eur J Nutr. 2016;55(2):25-43.

- Nguyen M, Jarvis SE, Tinajero MG, Yu J, Chiavaroli L, Mejia SB, Khan TA, Tobias DK, Willett WC, Hu FB, Hanley AJ, Birken CS, Sievenpiper JL, Malik VS. Sugar-sweetened beverage consumption and weight gain in children and adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies and randomized controlled trials. Am J Clin Nutr. 2023;117(1):160-74.

- Ma J McKeown NM, Hwang SJ, Hoffman U, Jacques PF, Fox CS. Sugar-sweetened beverage consumption is associated with change of visceral adipose tissue over 6 years of follow-up. Circulation. 2016 Jan;133(4):370-7.

- Malik VS, Pan A, Willett WC, Hu FB. Sugar-sweetened beverages and weight gain in children and adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013;98(4):1084-102.

- Hu FB. Resolved: there is sufficient scientific evidence that decreasing sugar-sweetened beverage consumption will reduce the prevalence of obesity and obesity-related diseases. Obes Rev. 2013 Aug;14(8):606-19.

- Kaiser KA, Shikany JM, Keating KD, Allison DB. Will reducing sugar‐sweetened beverage consumption reduce obesity? Evidence supporting conjecture is strong, but evidence when testing effect is weak. Obes Rev. 2013;14(8):620-33.

- Trumbo PR, Rivers CR. Systematic review of the evidence for an association between sugar-sweetened beverage consumption and risk of obesity. Nutr Rev. 2014;72(9):566-74.